Raphael’s “The School of Athens” is probably one of his most glorious and distinguished works that he produced during his successful, but sadly short career. It displays many of the techniques and artistic evolutions brought about in the late 15th and early 16th centuries during the period of the high renaissance, making it an excellent example of work originating from this period in history. This particular fresco stands out for me, in comparison to his other works as a pinnacle among his paintings. I will explain why this image fascinates me so and attempt to analyse how the School of Athens stands forward in contrast to its neighbouring frescos.

At the beginning of the 16th century the Popes Julius II and Leo X commissioned grand and often challenging projects from the gifted architects and artists of the age. The two artists that stand out in this regard were Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) and Raphael (1483 – 1520). Michelangelo produced works that demonstrate an extensive knowledge and understanding of human form and anatomy. Raphael was certainly not lacking in this area of expertise and I presume that Michelangelo’s artistic prowess had inspired Raphael in his own study of human realism.

The School of Athens was painted in the Stanza della Segnatura at the Papal Palace in the Vatican, where it remains in all its glory to this very day. It is a part of a series of frescos commissioned by Pope Julius II for his private quarters within the palace. The paintings in this particular room, which was used as the Popes personal library, are meant to represent the different sections of knowledge. The School of Athens being a portrayal of Philosophy. The other frescos adorning the adjoining walls representing Religion (Disputa), Poetry (Parnassus) and Law. (Paoletti & Radke, 2011) . It is thought that the books relating to these subjects were situated below the corresponding painting. (Bragg, Hobbs, Rees, & Kraye, 2018).

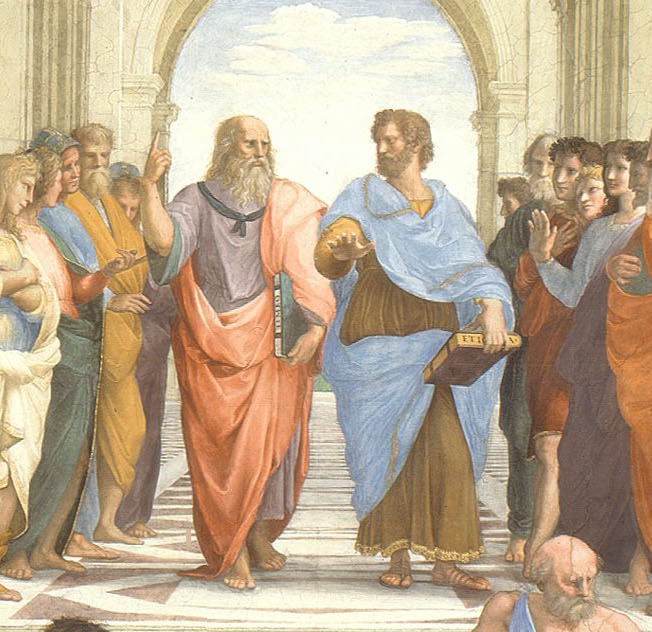

The painting depicts an arrangement of figures set inside a grand architectural structure, this extends back in perspective to where the blue sky can be seen through the arches in the background. The upper portion of the image lends itself to a symmetrical composition that blends with the arc of the wall on which it is painted. The distribution of the subjects into varied groups contained in the lower portion are in contrast with the simplistic symmetry of the above.The central focus of the painting depicts the two philosophers Plato, who is painted in the likeness of Leonardo Da Vinci (1452 – 1519), and Aristotle. Plato, who is gesturing upwards, is depicted as if to portray the idea of Platonic thought. Aristotle, with his arm outstretched and his palm pointing towards the floor, seems to signify his captivation with natural phenomena. (Honor & Fleming, 2009).

The surrounding figures are positioned with varying ambitious poses, which differ from the more static anatomic arrangements from the Byzantine and the Medieval periods. This brings me to reminisce on the opposition of poses between the energetic forms of Hellenistic and the simplistic composition of Greek Archaic sculpture. It fascinates me how the separate groups provide their own narrative within the image as a whole. Included within the crowd, some acclaimed scholars add to the already bustling narrative. Diogenes is said to be represented by the splayed-out figure upon the steps, and Averroes, the Muslim philosopher, is thought to be looking over the shoulder of Pythagoras on the left. The academic situated towards the lower right of the image holding a globe is believed to be Zoroaster, the Iranian prophet. Within the group of conversing men where Zoroaster is in discussion, Raphael included a self-portrait of himself. He is depicted as looking directly at the viewer which in turn brings me to a feeling of emotional connection, almost as if I am looking at this painting with himself at my side.

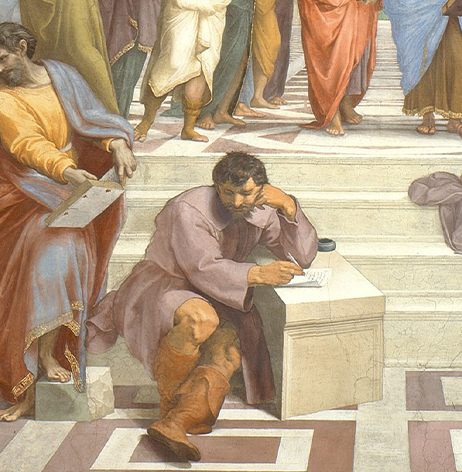

Another point to discuss about this painting is the absence of a figure in the original cartoon (initial drawing that is transferred on the surface before the painting takes place) for this fresco. The pensive scholar who is leaning on a marble slab in front of the steps is thought to represent Heraclitus of Ephesus (also believed to be the likeness of Michelangelo). However, the subject was missing from the original composition drawn out in the preparatory drawing for this painting. It is understood by art historians that the figure of Heraclitus was added into the painting after it was initially finished.

There are so many aspects of interest to this image that excite and inspire me. The fashion in which Raphael designed the composition to compliment the shape of the surrounding architecture. I admire the colossal scale of the background with its deep sense of space and perspective. Bright colours and ambitious poses bring the eye across the bustling narrative of the lower portion of the painting. Such a busy scene that gives no rest for the eye. And I must also acknowledge the subject matter. The small fragments of meaning behind each subject provides a good quantity of potential conversation between art historian and pupil.

Works Cited

Bragg, M., Hobbs, A., Rees, V., & Kraye, J. (2018, August 11). Retrieved from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7S2XD9SYoeg

Hodge, S. (2017). The Short Story of Art. London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd.

Honor, H., & Fleming, J. (2009). A World History of Art. London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd.

Paoletti, J. T., & Radke, G. M. (2011). Art in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom: Laurence King Publishing Ltd.